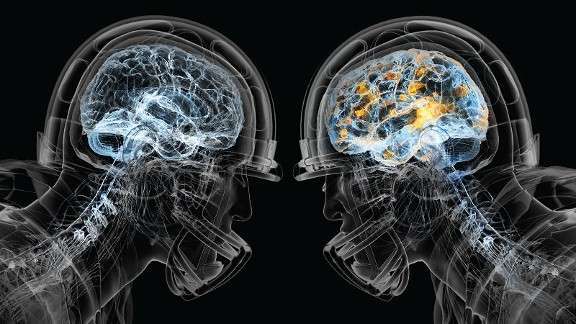

The term CTE or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy is a well-known term used to describe a condition found in people whose brains have been exposed to severe concussive and subconcussive trauma for years. Those brains, damaged by the trauma, are found to have high concentrations of a protein called p-Tau which has become the hallmark of the disease. The issue is that even today, the condition can only be identified after the person’s death.

The fact that the protein can only be identified post-mortem has caused the scientific community to expend enormous resources to be able to identify CTE in athletes while they are still alive. The focus has been on being able to identify the accumulation of Tau proteins or other “biomarkers” that the medical community can use to diagnose and treat the disease.

While there have been several promising studies, none have produced a test that can identify the disease.

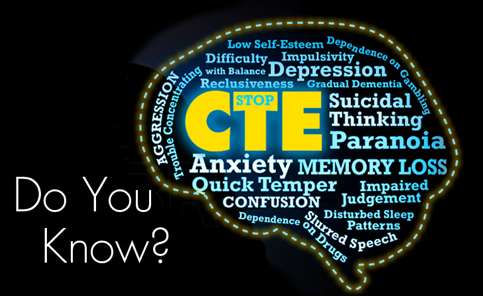

he problem with focusing on biomarkers or other live indicators that prove an athlete has developed CTE stems from the fact that the primary evidence of the condition, the p-Tau proteins, have not been shown to cause any specific symptoms of a disease. While CTE is graded in stages, those stages are based on the damage done to the brain, not conditions or symptoms that have been definitively associated with the amount of damage sustained. In fact, while there are associated symptoms with each stage as listed by the Concussion Legacy Foundation, those symptoms, primarily psychological

disorders, were reported by the athlete or their family and/or associates prior to his or her death. (Yes, female athletes also can acquire the disease).

This approach to CTE has ensured that the public’s perception of the condition is one that is:

- Associated with professional football players and

- Can only be diagnosed after death.

This perspective is in fact dangerously incorrect and has resulted in the continued and unnecessary exposure to concussive trauma for millions of American kids and has contributed to one of the largest, preventable epidemics of mental illness in the United States.

The fact is that CTE does exist, it is a real disease with a direct correlation to repetitive concussive and subconcussive trauma. The presence of p-Tau and other abnormalities, while not directly associated with health issues from a causality perspective, are indicators of significant concussive and

subconcussive trauma that results in brain damage that has been definitively linked to psychological and other mental health issues for decades.

These disorders such as depression, substance abuse, aggression, impulsivity, mood swings, suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, and more have been tied through research and studies to the exact type of trauma and damage done to the brain by contact sports.

Look at any NFL player or other professional athlete who has succumbed to CTE and you will find these symptoms as well as a deterioration of a

once-promising life. Every year, hundreds if not thousands of young American athletes suffering from CTE-related mental illness take their lives, and hundreds of thousands more have been, or are, in counseling, psychiatric care, jail, or are suffering in silence.

CTE is about mental illness, not p-Tau proteins. The link between brain damage because of CTE and resulting psychological issues is key to identifying the disease while the athlete is alive and able to hopefully intervene at an age where the damage and future progression of the disease can be mitigated. Like Alzheimer’s, which also cannot be definitively diagnosed until after death, CTE could be clinically diagnosed based on displayed psychological disorders and an assessment of an athlete’s subconcussive and concussive history.

However, with medical, athletic, coaching and parental communities considering CTE a rare disease instead of one that is causing brain damage and psychological stress to countless children and young athletes on a daily basis, there is a huge awareness and education gap to address. Current changes in the focus of research on CTE from p-Tau pathology to identifying damage to specific parts of the brain shown to be linked to mental illness like myelination, synaptic density and the pre-frontal cortex demonstrates the need to address this awareness gap through science and provide the evidence necessary to further educate and train our society.

Now is the time for society to recognize CTE as a threat to our children’s and young athletes’ well-being. Instead of a posthumous disorder, CTE should be defined as a “degenerative neurological condition shown to cause damage to the brain that has been linked to mental illness”. By redefining CTE as a disease that causes mental illness, society will hopefully wake up to the inherent dangers of exposing a child or young brain to continuously repetitive head injuries and make the changes necessary to protect our youths from harm.

No contact sports till 14…any takers?

Written By Bruce Parkman

Founder of the Mac Parkman Foundation for Adolescent Concussive Trauma and the author of the book “Youth Contact Sports and Broken Brains”. He is also an entrepreneur, Green Beret Sergeant Major (ret.) and semi-professional rugby player.